Wehrmacht Hero Blurb

That's all we remember, Karl...

StuG III ausf. F

- Train station, Stalingrad, Russia, USSR

- September 14th, 1942

- 2 Zug, StugAbt 244, 113. ID, 6. Armee

- Oberwachtmeister Karl Pfründtner

Some moments of the Second World War are documented second by second, for example the Dunkirk pocket or Operation Overlord; those have been analysed and wargamed to death. Some people, or times, are remembered only as single lines of slightly questionable text. One of these blurbs was about a StuG officer, Oberwachtmeister Karl Pfreundtner, the commander of StugAbt 244's 2nd Zug. He did something right, at some point, and this is widely celebrated by repeating the same information almost everywhere. Do a cursory search on the man, and you will see:

„Probably the most successful engagement involving Sturmgeschutz III Ausf F took place in Stalingrad in early September of 1942. Stug III Ausf F from Stug.Abt.244, commanded by Oberwachtmeister Karl Pfreundtner destroyed 9 Soviet tanks in 20 minutes. On 18 September 1942, Oberwachtmeister Karl Pfreundtner was awarded the Knights Cross for this achievement."

...and not a lot more. To be fair, his was a small unit and none of them survived. As they say, dead men tell no tales. The problem in this case is that I know of two occasions, within a reasonable timeframe, when Karl might have had his day, but I can't be sure.

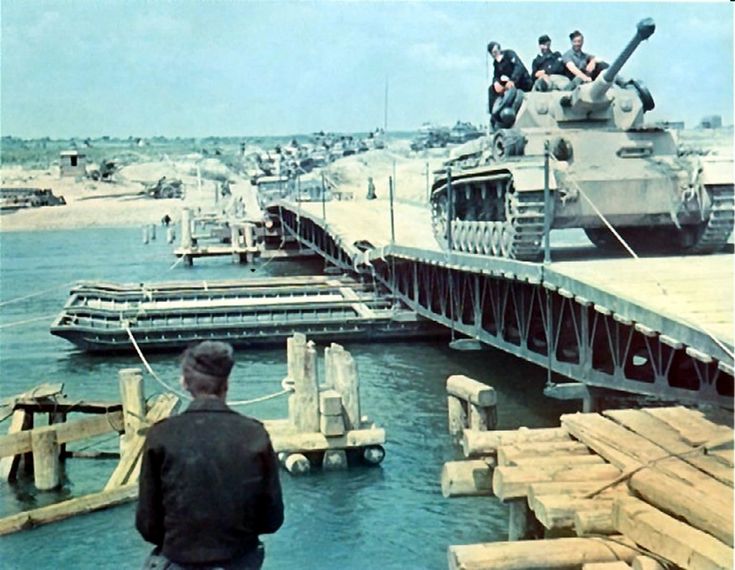

- His unit was assisting the 384. Infanterie-Division with their crossing of the Don river near Nizhnegerasimovskii on August the 16th -my birthday!- and it's mentioned that "he contributed significantly to the establishment of the first 6. Armee bridgehead across the Don river by the 384. Infanterie-Division."

- A month later, on the 14th of September, his unit reinforced Colonel Friedrich Roske's 194th Infantry Regiment for its drive to the Volga. However, they got stuck at the Stalingrad Central train station when suddenly, the shit hit their fan: bombs going off, T34s racing around, machine gun fire everywhere. In the confusion, I'm pretty sure he (or they) shot Vladimir Khazov.

So now I can decide. That doesn't sound like proper research! It's a good thing I'm not a professional historian, then... No, I can use my imagination. (If you do know - please enlighten me with proof!) Fortunately, we're aware of a lot of meta stuff, like where 6th Army was and where the Don lies, so I shall therefore improvise. I'm going to tell you a story, and I'm sure it's going to be at least slightly wrong. Which is fine with me.

Dolchstoß

Karl was born in Munich in the year nineteen-twelve, just as the world was about to change. His parents -let's call them Heinrich and Käthe- had high hopes for their son, hoping he'd become a doctor or a celebrated pianist. But fate, as it often does, had other plans. His dad -Heinrich, the mailman- was drafted to serve in the Great War. He didn't make it back, blown to pieces by a French seventy-five. Then the damned Englishmen threw up their blockade, and there was no more food. Like so many German civilians, Käthe, her boy and their country suffered for years and then they lost the war. Karl, who was only six at the time, just knew that he was hungry, and that his mother was sad. Later, he was sent to the Luitpold-Gymnasium, where he first heard the whispers of betrayal; Germany had not been defeated by superior Allied forces! No, instead, his friends informed him that the German Kaiser, and his armies, had been nefariously stabbed in the back by feeble politicians and treacherous Jews. Those same friends introduced him to the Hitlerjugend, where he found the security and structure he was missing at home. He joined the organisation and was swept up in the developing storm.

Like so many others, he wanted to be proud of his country, not to see it trampled beneath the boots of foreigners, or sold to evil Jews! Now it was time for Germany to shine, to stand up after the Versaiiles abuse. They needed to show the world that Germans were the best and strongest humans on our planet. He felt good about that, and about himself, which was something new after all these years of poverty and misery. No, this mister Hitler was going to make Germany great again, and Karl was going to do his bit! However, as Karl wasn't the toughest kid on the block, he didn't qualify for the elite SS or the Luftwaffe. But the Wehrmacht took him in, assigning him to an artillery regiment. And later, when someone had the bright idea of a turretless tank, a StuG, Karl found himself in one of those, rumbling across the battlefield.

"If you want to live, you have to fight. That's the law of this world. If you don't want to fight, you have no right to life."

Barbarossa

Karl no longer heard the rumble of the StuG's engine; it was just one of the sounds of this war. He'd been in the cramped vehicle all week, his eyes scanning the horizon for the enemy. The flat expanse of Ukrainian farmland stretching out before him, a vast, empty canvas waiting to be grooved by their tracks. Beside him was Heinz, his loader, nervously tapping the 75mm rounds for their short-barreled gun. In front was the driver, Franz, really still a boy. He gripped the steering levers, his eyes fixed on the field ahead. Their StuG-Abteilung -number 244- was on the move, part of the spearhead of Operation Barbarossa, the massive invasion of the Soviet Union. The air was thick with anticipation, a mixture of excitement and fear. They were about to cross the border into the Soviet Union, a land of vastness and mystery, a land of enemies to be conquered. The border came and went without a fanfare, just a line on a map, an invisible barrier between two worlds. They rolled on, deeper into Soviet territory, the landscape growing more rugged, the forests denser, the villages more rustic.

The first sign of resistance came in the form of a lone Soviet BT-5 tank, suddenly emerging from the bushes and its turret swiveling towards them. As Karl's heart pounded in his chest, he barked orders at his gunner and driver. "Franz! Move left, quick!" and "Heinz! Feindpanzer at two o'clock! Load and..." BOOM! Heinz understood his business and sent an HE shell towards the Christie machine. The shell struck the Soviet's armor, leaving a smoking hole in its side. The Soviet tank lurched, its suspension slumped, and then the BT started burning with its crew trapped inside.

The Abteilung advanced further into the Soviet Union, pushing through scattered pockets of resistance, their trusty StuGs leading the charge. They captured villages, their inhabitants cowering in fear, their eyes wide with bewilderment. They took prisoners in the hundreds of thousands: Soviet soldiers surrendering without a fight, their faces sad and confused. At night, they camped under the stars, under the vehicle or on it's engine deck if it was cold. They ate from the Gulaschkanone, their stomachs grumbling and their minds filled with the day's events. They talked of home, of their loved ones, and of the war that seemed to go along so nicely. Indeed, despite the hardships of combat, there was a sense of optimism, a belief that they were winning, that they were fighting for a just cause, as they crossed into Russia itself.

Mr. Freeze

Our German Sturmgeschütz crew had slept in their vehicle, to protect them from the icy November wind. Now, they were outside, inspecting their vehice. The temperature had dropped overnight, and their Sturmgeschütz' road wheels were now frozen solid in the mud. "Verdammt!" The driver kicked the rear sprocket, and immediately started hopping on the other foot. And cursing, a lot. "Fuck this shit! We're going NOWHERE in this thing!". He kicked, again. "Now, Franz, you're not making your mother proud with that kind of language.", his commander said. "But maybe you're right about moving." Karl stood up and looked around him. His little microcosm was repeating itself all around him. His Abteilung was immobilised, frozen, stuck. Yesterday had already been bad, yesterday the mud was gloopy and thick. Now, it was solid. "Boss?" Karl looked up at Albert, his radio man, who was standing on top of their StuG. "What's up?" "I can see Red Square from here. See?" He pointed. "That's the domes of Saint Basil's, right there." Karl squinted in the morning sunlight, and he did see. Moscow was right there, ripe for the taking, as their Führer had predicted. "I do see, and all we have to do is kick the door in. Got to find a way to get this thing moving..." He looked from the StuG's muddy idler wheel up at Albert, just in time to see the man's head explode in a pink mist and gruesome splinters, closely followed by a distant BANG! "Fuck! COVER!" Karl's eyes were scanning the treeline, to the north. That was the only bit of cover so if he were the sniper, he'd shoot from there. No one - flash! Bang! Another soldier dropped - reacted too slow, and died as a result. Usually, Karl would swing his gun around and treat the bastard to a Kartätsche shell, but as his StuG was StucK, so that was not going to happen. Damn, he couldn't even drive away. Also damn, he was getting tainted by Franz' swearing. Mutti wasn't going to like that.

Karl didn't know yet, but they were in for a rough day. The Battle for Moscow had just started.

I'm blue / Da ba dee da ba di

A week later, Hitler received a strange message. German troops were falling back, not to say retreating. RETREATING? Why? Well, for example, the commanderof III Panzer Corps, von Mackensen, "had reported several weeks earlier, before the last advance began, that his two divisions, the "Leibstandarte" and the 13th Panzer, were worn out, short on everything from socks to antifreeze, and down to a half to two-thirds their normal strengths." This was impossible! However, after checking with von Kleist and Dietrich, the LSSAH commander, Adolf seems to magically forget about what's going on. Suddenly, he's much more interested in next year's Grand Plan. It seems to me that he couldn't take the news that the German troops weren't winning, and he just zoned out for the winter, leaving combat to the Generals. Which, it must be said, was a good idea in the first place.

Basically, he had three options:

- Capturing Leningrad would be a massive blow to Soviet morale and mean the loss of a lot of heavy industry, but would have little other strategic value.

- There would be no capturing Moscow, that city would be fully ausradiert. That would severely mess with Soviet politics, organisation and communications, but it was an extremely hard, fanatically defended target, especially as the German troops were exhausted after 1941's failed attempt.

- Or, he could go for the southern oil fields at Maikop and Grozny. Denying oil to the Soviets would mean the end of their operations, and help the German war effort. However, such a deep penetration into enemy territory meant that flank attacks would be likely.

His generals preferred a second attempt on Moscow, which is perfectly reasonable. It may also have turned into the same kind of meat grinder that Stalingrad was - we'll never know. Hitler, who only listened when it suited him, preferred the southern option. However, to prevent the expected flank attacks, he reinforced AG Süd with units from the North and Central Army Groups, and split it into two Heeresgruppen - one to take the oil, and one to protect the flanks. Now have a look at some map, find Voronezh (where the operation -Fall Blau - started) and head south-east. What's the first major city you see? Right, 500 kilometers away. Stalingrad.

At the start of the operation, the Germans noticed something strange. Where previously, the Soviets had been caught in massive encirclements and fighting like headless chickens, they were now retreating in somewhat good order, trading space for, well, time and dead Germans. Slowly, the German army found out that supply lines stopped working after a thousand miles, that horses are NOT the answer and that maybe, just maybe, the Soviets weren't completely useless sub-humans after all. The Wehrmacht was slowly being eaten away. The Soviets suffered far worse losses, but they had millions more men to spare and as today, their leadership just did not care. This way, the envisioned Blitzkrieg-to-the-South became a violent slog, creeping forward in the hot summer - German soldiers advancing in their underwear! Soldiers, tanks and supplies were disappearing at an alarming rate. In fact, by the time they reached the Don, the German army was at about half strength, with Adolf only seeing unit counters and believing them to be at 100%. As in so many cases (and with 20/20 hindsight), this battle was decided before it even started.

But why was there even a battle? I mean, there was a Battle for Kharkiv -several, in fact- and the same for Rhzev, even the Battle for Berlin isn't universally remembered as the monumental clusterfuck that was Stalingrad. It's not like the city had much important industry, or bridges, or was in the way of another important target, say Moscow. They could have just ignored it, or encircled it like they did with Leningrad. However, it was called STALINgrad. We're talking dictators here, both Adolf and Josef. They just HAD to have the biggest dick, and were fully prepared to sacrifice thousands of their soldiers to prove their superiority. (I just have to add that Stalin's role in the Battle of Tsaritsyn, the town that would later bear his name, was rather unimpressive; in fact, he screwed up, black-marketed supplies, executed useful people, seriously dissed Trotsky and was recalled. "In the countryside, he burned villages to intimidate the Russian peasantry into submission.", says his biography, which shows a bit of what kind of guy he was.)

In fact, after Rostov-on-Don fell to the Germans, Stalin issued his Order No. 227: “Not one step back!” Anyone who retreated from the enemy, soldier, woman or child, would be considered a traitor and shot. In Stalingrad, this meant the civilian population (and a LOT of refugees) was not allowed to evacuate, that soldiers could not make tactical retreats, and that the Volga was the end of the world. We'll never know how many mothers and children were killed; not only by Germans, but also by Soviet artillery and carelessness. Only after the Luftwaffe had laid waste to the city, Stalin grudgingly allowed the noncomattants to leave. Likewise, Hitler also fully planned to kill the city and all its inhabitants, proving the two were more alike that they cared to admit.

Karl meets Gulya

It's now the 15th of August and the front line in the Don bend runs roughly from Logovskii in the North to Malonabatovskiy in the South. The Germans had been pushing hard, costing them a lot of men and supplies, but their morale was good, even if it was still bloody hot. The Soviets, however, were on the verge of collapse. When German reserve units started leapfrogging forward, they punched through Soviet lines with ease, pushing them back tens or twenty kilometers. Soviet Guard units were ordered to attack, but their strength was diluted along the front line and their efforts went largely unnoticed. Well, that is, someone must have noticed that the Soviet 341st infantry division alone lost eight and a half thousand men...

Let's get back to Karl and his crew. They've been redeployed to the south. Dead Albert was replaced by "the boy" Rüdiger, and they received a new StuG model F, with the longer L/43 gun. As we speak, they're camping out in a clump of trees, on a ridgeline about five kilometers west of Podonokigrad. No shops, no bars, no women, there is literally no one around but tired and hungry Wehrmacht men. Seriously, have a look at Nizhnegerasimovskii (which is what it's really called). Back then, it was five houses, a barn and a dead horse. And when Karl was there, even no enemy around. So Karl made a fire -carefully!- and grilled the scrawny little pig that Franz shot earlier. Their regiment (113. ID) was still near Kletskaya, to the north-east, guarding the line against Soviet flank attacks. And because you don't need armoured vehicles just to sit around, they were lent to another regiment, the 384th.

The Don is about 300 meters wide at that point, and the crossing forces were being shot at. After some recon units had secured the east bank, crossing in rubber boats, their engineers built a heavy pontoon bridge for the trucks and Panzer. While being shot at, of course; river crossings are about the hardest thing in warfare. You're trying to get across, and it's hard to fight while rowing. Also, someone might shoot you boat! Anyway, with StuKa and lots of artilley support, they managed to set up a bridgehead near Panshino. Have a look, there's a monument there. Strangely enough, this monument is for a dead actress, Gulya Koroleva. If you believe Soviet propaganda, which I most sincerely do not, she decided to "help our Great Leader trample the facist hordes" by becoming a nurse. When they brought in a bombed-out child, minus an eye, she left her own child to become a front-line medic with the 214th Rifle Division, at Panshino, opposite the bridgehead where Karl was getting ready to roll. Soviet records say she died here, where her monument is, on November 24th during Uranus, but I'm sure she saw action before that. In fact, she was interviewed about it, and you can't be interviewed when you're dead. Or maybe you can, in Soviet Russia.

As she said: "We and the Fritzes fought all day for the same hill. They occupied it several times and retreated several times, but in the end they occupied our hill. I went out to retrieve our wounded - close to the Germans. They noticed, they tried to take me alive. I crawled away, they tried to follow and shot machine guns in my direction. I crawled back in their direction, taking a grenade in my hands. Slowly, quietly, I came closer and threw my grenade. I killed two of them with it!" I imagine Karl and his boys were not at all happy about this. His Abteilung's StuGs were dug in and camouflaged, ready to take the counterattack when some silly bint lobbed a grenade at them.

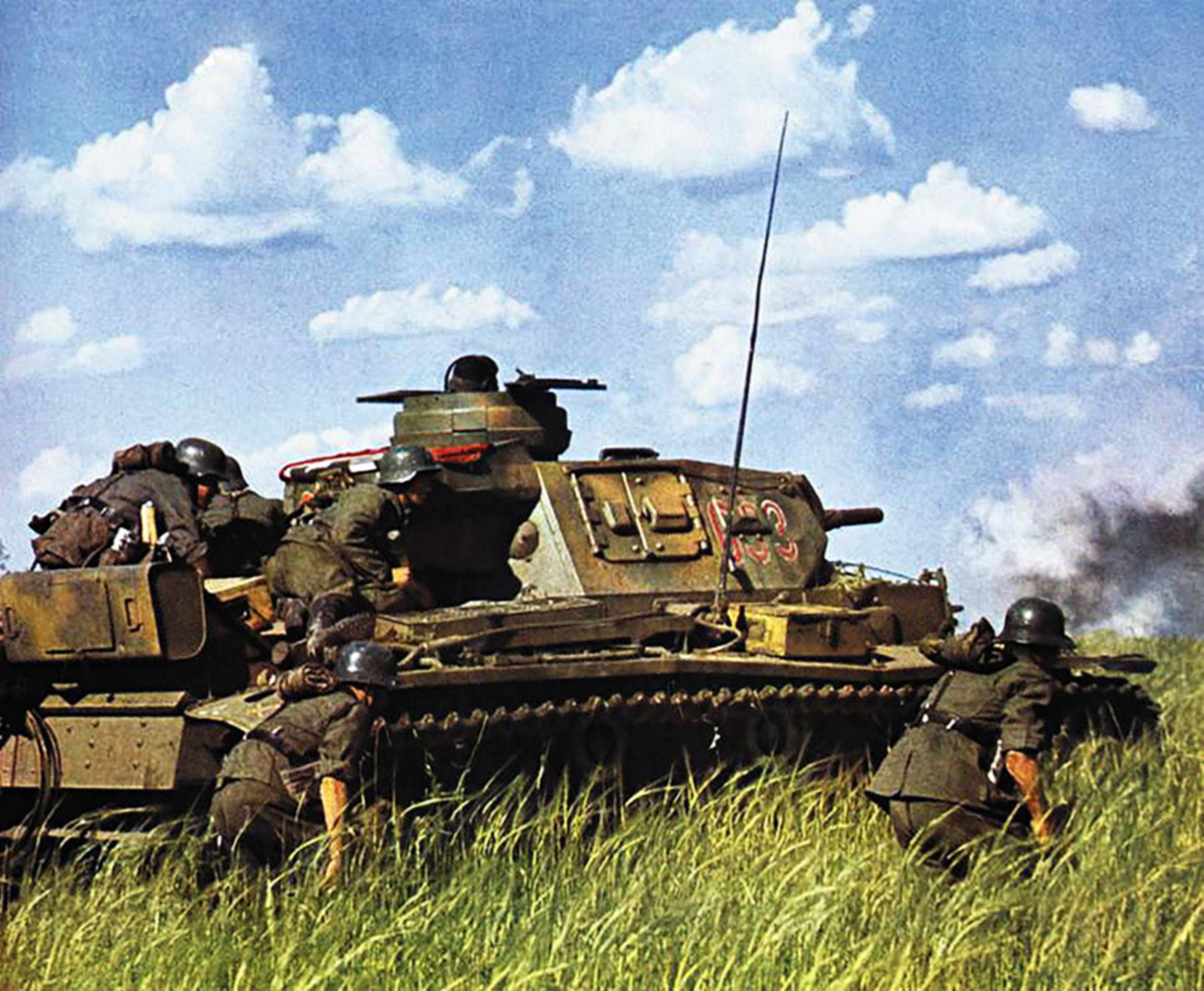

Then, suddenly, the Soviet 22nd Tank Division rushed in for the attack with their 28 radio-less Mickey Mouse T-34's, buttoned up and screaming "Urrah!". This is normal, because those early T34s had a two man turret crew, no cupola and no radio, meaning the commander was also the gunner and flag man. Soviet commanders had a lot to do, and a habit of getting their head shot off if they stuck it out of their tank. They never saw 244's assault guns. Karl's crew, in a good spot, still pissed about the grenade, killed nearly half of them.

In the North, however, Soviet forces continued to push at the German flanks, crossing the Don several times. This cost them around two hundred thousand (!) casualties, but weakened the Germans too, and kept them off balance. The Wehrmacht clearly had not secured the area, something they really needed to do before their attack on Stalingrad. That city was their final, definitive target; as far as I know, the German designs on Lebensraum ended at the Volga, at least, for this generation. They should just have taken the time to get their shit in order, but I guess Hitler was just not a patient man. He sent his already weakened forces towards the city, arriving there at the beginning of September.

The train station

Gumrak airfield is slightly higher than Stalingrad itself, but you can't see the city from there. Karl was leaning against his StuG, picking at his teeth with a wood splinter. Toothpaste was a long time ago - and his gums were bleeding. "Damn this, not enough vitamins.", he thought. "Just like at home." Home, his mother. So far away. Suddenly, he wanted to cry, but didn't. Tough Nazis don't cry, he was sure. He was even beginning to doubt that he WAS a Nazi, he didn't really remember what the fuss was about. Jews are bad, m'kay, and don't mention the war. Here he was, two and a half thousand kilometers of mud and dust between him and his mother. Not sure what he was doing here, either. 244's 2nd Zug -his unit- was still on loan, he hadn't spoken to his colonel in weeks, he didn't know what to do, or who to follow.

"Pfründtner?"

"Oberst...?"

"Roske, 194th Infantry. I need your help."

"Well, Oberst Roske, I need fuel, and shells for my gun. Can we perhaps help each other?"

"Pfründtner?"

"Oberst...?"

"Roske, 194th Infantry. I need your help."

"Well, Oberst Roske, I need fuel, and shells for my gun. Can we perhaps help each other?"

A little to the North, Hube's 16th Panzer had already ploughed through the Soviet defences, reaching the Volga near Latoshinka. To the south, 14th Panzer was doing the same near Kuporosnoye, almost completely encircling the city. Karl's combat group was in the center, pushing east along the Tsaritsin gorge. This greatly annoyed Yeryomenko, the Soviet commandeder, who ordered Chuikov "to do something!". Chuikov, who was actually being shot at, never expected a counterattack to work, he just hoped to disrupt the enemy's plans. The enemy, in return, disrupted Chuikov's plans by bombing his kitchen. Hungry and tired, he was forced to move, in darkenss and under fire, to his command post on Mamayev Kurgan, where there is now a very large statue of a lady with a sword.

We're on december 13th now, and unbeknownst to the Germans, Zhukov is having tea at the Kremlin, discussing the future Operation Uranus.

Early in the morning, before civilised people wake up, the Soviets attacked. Chuikov had been right, the Wehrmacht was unimpressed. They stopped the attack by dawn and chased the Soviets via the railway line towards the residential area of the Zapolotnovksy district. Roske ordered his troops to advance, supported by the StuGs and the Luftwaffe, and smash their way into the city. He wanted to reach the embankment of the Volga, where the ferries arrived from the Volga's east bank, carrying soldiers and supplies. When they advanced into the area where the city's workers lived, they (and the remaining workers) were immediately bombarded with tube artillery and Katyusha rockets. The whole district was ablaze, and many civilians died in the chaos. The Germans were hurt too: they started losing more and more people to unexpected hand grenades and invisible snipers. Roske achieved the seemingly impossible, even with the disastrous “friendly fire” StuKa attack that wiped out one of his companies: his men pushed past the Khorovod statue, past the station and Univermag, towards the river, where they managed to capture the House of the Specialists, overlooking the Central Landing Pier.

Roske had his command post beside the church. Paulus, Seydlitz and a few generals were already there. And they waited for me to come up and bring Volga water. And when I came up, they were quite disappointed that I had no frogs in my hands. Anyway, they were surprised that I didn’t even have a bottle. I reported we cannot go down in daylight. As soon as we raise our noses above the high banks, bullets whizz around our ears. They were quite disappointed."

Chuikov, in his HQ 800 metres further south, used everyone he could find to prevent the Germans from taking more. According to Roske, "Something unexpected happened"; there was confusion. T34s were speeding around, mortars and machine guns fired. A chaotic Soviet counterattack started, trying to re-take the station! Karl's StuG was nearby, looking along Kursk street, when suddenly a wild T34 appeared. Again, I'm writing a story here, it's based on historical events (like all those whiney woman movies) but not necessarily true. Could be, though. I'll go with "that T34 was commanded by Lieutenant Vladimir Khazov", who actually died there, on that day. Karl's gunner saw the Soviet tank coming, and instinctively squeezed off the pre-loaded AP round when it drove past his gun barrel. Smoke! Fire! and flying metal sparks, killing at least three Soviet dismounts. T34's have fuel tanks inside the crew compartment, which you might think is a problem, and it is. The fuel spattered all over Vladimir, who was starting to burn. He jumped out, started rolling and was shot by some Fritz asshole with an MP-40. Karl, meanwhile, was trucking his StuG along, looking for more targets.

Within 24 hours, however, Roske and his men were fighting for their lives. Chuikov had ordered a fresh Guards division of 10.000 men across the Volga, to retake the city center. Roske’s men tried to hold off the Soviet assault, but in the end they failed. The Soviets retook the train station, and they would keep it for the rest of the war. If ever there was a Marne moment in the Second World War, this is it. It was the furthest they would ever get, and most Germans here would never see their home again. Kurt seems to have been lucky, though: he was wounded on the 10th of October and flown back to safety, to a hospital. Maybe, he even had the chance to go home and see his mother. Let's hope so, because he was sent back into action when he got better, and died in June 1944 during the Rogachev–Zhlobin offensive.

Biblio

- Stürmgeschutze: Armoured Assault Guns, Bob Carruthers

- Death of the Leaping Horseman, Jason Marks

- http://www.wwii-photos-maps.com/

- stalingrad.ru

- Moscow to Stalingrad: decision in the east, Earl Ziemke + Magna Bauer